The term climate grief has emerged over recent years to describe a complex emotional response to the climate emergency. The science and projections regarding climate change make grim reading. The ICCP report from April 2022 highlights that unless in the next 3 years drastic measures for decommitting from fossil fuels are taken, the window of opportunity to curtail the worst consequences of climate change will be missed.

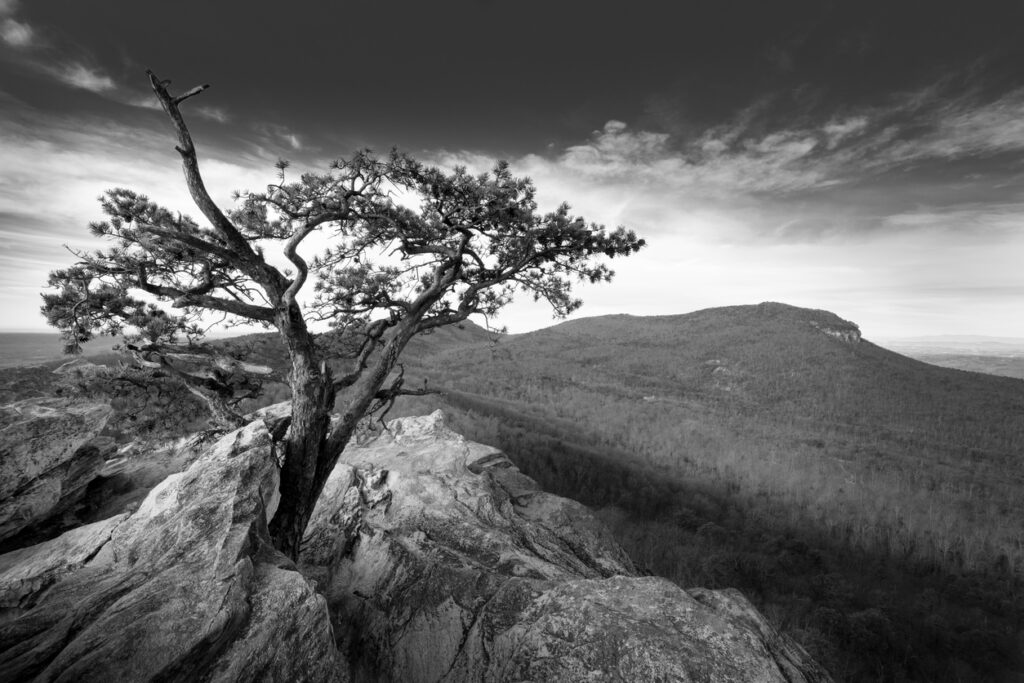

A world that might have been is slipping out of our reach

Movements such as Extinction Rebellion announce the looming end of civilisation, meanwhile others are pursuing an agenda of climate change denial. The Russian invasion on Ukraine has led to governmental thinking that fossil fuels are needed to compensate for energy disruption resulting from sanctions and supply issues. The rises in Antarctic temperatures are unprecedented, giving shape to the sense that humanity is standing on the edge of far-reaching adverse changes resulting from climate change. The existing changes in climate highlight the potential risks of polar melting; the emergence of extreme climate events leading to tipping points and rapid and catastrophic changes to the ecological systems that currently support human food production.

The bright future many grew up with during the 80s, 90s and even early 00s seems increasingly unachievable. A world that might have been is slipping out of our reach, with future generations facing the consequences of humanity’s inability to act in time to prevent catastrophic climate impacts.

This is the context for climate grief

Climate grief is a psychological reaction to climate change, stemming from any of the following:

-

Direct experience (e.g. wildfire/flooding)

-

Indirect effects (e.g. economic costs, productivity, social disruption)

-

Awareness of the science and expectation of adverse impacts in the future.

Researchers Ashlee Cunsolo and Neville R Ellis (2018) define it as “the grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems, and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change.”

When understanding climate grief, we can draw on what constitutes normal grief reactions based on Kubler Ross’ model of the five stages of grief, including emotions of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. While there are some similarities with ordinary grief, climate grief in some ways cuts more deeply existentially to the core of cultural and social identities, rather than just individual relationships.

Climate grief is associated with physical or ecological losses, and the subsequent changes to ways of life and culture, as well as the sense of place and belonging. In addition, climate grief may also stem from a perception of one’s own contribution or fossil fuel emissions to the existential crisis facing humanity.

Dealing with emotions of climate grief is an important first step before anything else. Feeling heard and seen with one’s climate grief can enable people to move beyond the denial, anger, and bargaining stages.

The environment is often taken for granted and, in many ways, society has created a bubble around human civilisation that creates the illusion of the environment as something separate. When threatened or even lost, humanity’s immersion and dependency on the environment become more salient and acutely felt. Reacting with grief to these threats is entirely understandable and justified.

Rather than viewing climate grief as a hindrance (due to the negative emotional experience), it can be seen as a powerful motivator for adaptive actions. Helping people overcome challenging and complex emotions created by climate grief should therefore be more than just about addressing difficult feelings. We should be facilitating and mobilising individuals and organisations to act in all their spheres of influence.

Climate grief in 2022

The situation in Ukraine has, for many people living in Europe, added a further element of grief, namely the grief for what was one of the longest periods of peace in Europe since the second world war.

Furthermore there was hope that the lessons learned from the rapid transformation and adaptation to Covid-19 might lead to a transformation of economic processes away from fossil fuels. Instead, governments and many businesses quickly elected to return to office-based working and settled back into a business-as-usual that allows for varying degrees of hybrid working but does less to retain reductions in emissions achieved during the lockdown.

On a brighter note, the speed at which organisations adapted should give some cause for hope. Translating the creative energies harnessed during the pandemic to climate change might imply there is a great deal that could be achieved by organisations in a relatively short time. What seems to be lacking is the visionary leadership and the political will to make these big changes.

Climate grief in this context is important because unresolved, unacknowledged, and unprocessed grief can impede decision-making and block the inspired action needed to progress more rapidly on climate change.

The role of climate cafés

Dealing with emotions of climate grief is an important first step before anything else. Feeling heard and seen with one’s climate grief can enable people to move beyond the denial, anger, and bargaining stages.

Sharing with others makes emotions more visible and can makes us feel less alone, isolated and powerless. In response to the mental health impacts created by climate grief, psychologists and psychotherapists have been developing climate cafes, which are real or virtual events that provide a safe space for people to share their feelings about climate change and express their emotions, perhaps reaching some acceptance, practising self-care, while also helping to ferment actions they might take in future. While this approach has been available in the UK for some time for example via the Climate Psychology Alliance, such approaches have not been used in workplaces to a large extent.

Climate grief alerts us to something important – that the future of humanity and life on planet Earth is being threatened.

Increasingly employees will be affected directly or indirectly by climate impacts, leading to grief and other mental health impacts. Armed with this certainty, employers need to support those affected as well as act proactively in response to other dimensions of climate change. It therefore might be worth considering the use of climate cafés in organisational settings for employees.

Climate café’s can provide opportunities for workers to share their feelings with others and be heard, leading to better wellbeing, as well as potential for motivation to contribute to change. Adopting the approach used for organisational coaching groups or 1:1 coaching could provide a tailored approach in line with existing L&D projects. Running climate cafe’s requires trained facilitators, which the Climate Psychology Alliance or some trained independent psychologists/psychotherapists can provide.

At a practical level there are a variety of issues to discuss, particularly relating to the creation of the safe space, and individuals disclosing sensitive information. This has bearings on how one might implement and organise climate café approaches.

(If any readers are interested in rolling out climate cafés, please connect with me on LinkedIn to discuss my research on their use within organisations.)

What else can HR do to support employees absorbed by climate grief and inspire action?

It is vital to acknowledge difficult emotions and the challenge of accepting what seems unacceptable. Alongside considering the use of climate cafés, there are a number of other ways organisations can tackle climate grief and take positive action:

- Business can and should provide opportunity for employees to cocreate climate change action within the business. This can provide employees with some control and agency, which in turn can support wellbeing. Quality circles and working groups for addressing climate sustainability can be agents for progress in this area as well as for business innovation and growth.

- Get with Project Drawdown, the world’s leading resource for climate solutions, which provides a diverse range of measures to support reductions in climate emissions. Drawing on the ideas, here businesses can contribute to initiatives such as tree planting, rooftop gardens, implementing water conservation etc. Other local projects (e.g. community housing) for addressing climate change can serve a similar role.

- Divest from fossil fuels as a priority to force fossil fuels out of the economic calculus. This is likely to influence employees’ mental health positively because they will feel they contribute less themselves to the ongoing environmental impacts caused by climate change.

- Signal commitment that aligns with carbon reduction measures: business travel restrictions on flights, reducing commuting, reduction of food waste. Commit to auditing energy consumption, supply, and distribution networks for opportunities to reduce fossil fuel emissions.

- Improve education for changing lifestyles at work (e.g. provide healthy plant-based food options, promote non-fossil fuel food preparation and reduce food waste). Benefits of such measures improve an organisation’s reputation as a socially responsible employer, but also carry benefits that extend beyond the workplace and potentially beyond an employee’s tenure. Such benefits enhance the reputation with former employees, and can translate into positive word-of-mouth marketing, as well as reduction in carbon emissions. A win-win situation.

- Check your mental health policies factor in climate grief as well as impacts on any other disruptions (for example the Russian invasion of Ukraine). Effective mental health policies should encompass disruption and have measures in place to enhance resilience and support of employees before and during crisis events.

- Implement proactive resilience strategies for developing effective responses to climate events and other disruptions. These can signal support, enhanced security for employees, and provide a meaningful approach for dealing with crises and their impacts on employees.

- Make time for tough conversations with leaders on climate action and support them in challenging shareholder apathy.

Climate grief alerts us to something important – that the future of humanity and life on planet Earth is being threatened. To act we must address the reasons for non-action, and we can only do this by addressing the difficult and complex feelings of being stuck emotionally with climate grief.

[cm_form form_id=’cm_65a14c3f5da64′]